Mental model: Docker packages the environment (config and dependencies) with the code, so “run” becomes a predictable, repeatable operation irrespective of the device and OS.

Mini command cheat sheet (the 20% you’ll use 80% of the time)

# Images

docker images

docker pull nginx:1.23

# Containers

docker ps

docker ps -a

docker run -d --name mynginx -p 9000:80 nginx:1.23

docker logs mynginx

docker stop mynginx

docker start mynginx

# Build your own image

docker build -t myapp:1.0 .

docker run -d -p 3000:3000 myapp:1.0Docker (First Principles + Hands-on)

This note is a cohesive “why → how → do it” walkthrough, based on the crash course I watched (YouTube video), and the hands-on custom docker image project (prasanth-ntu/docker-demo).

Key concepts at a glance (diagrams)

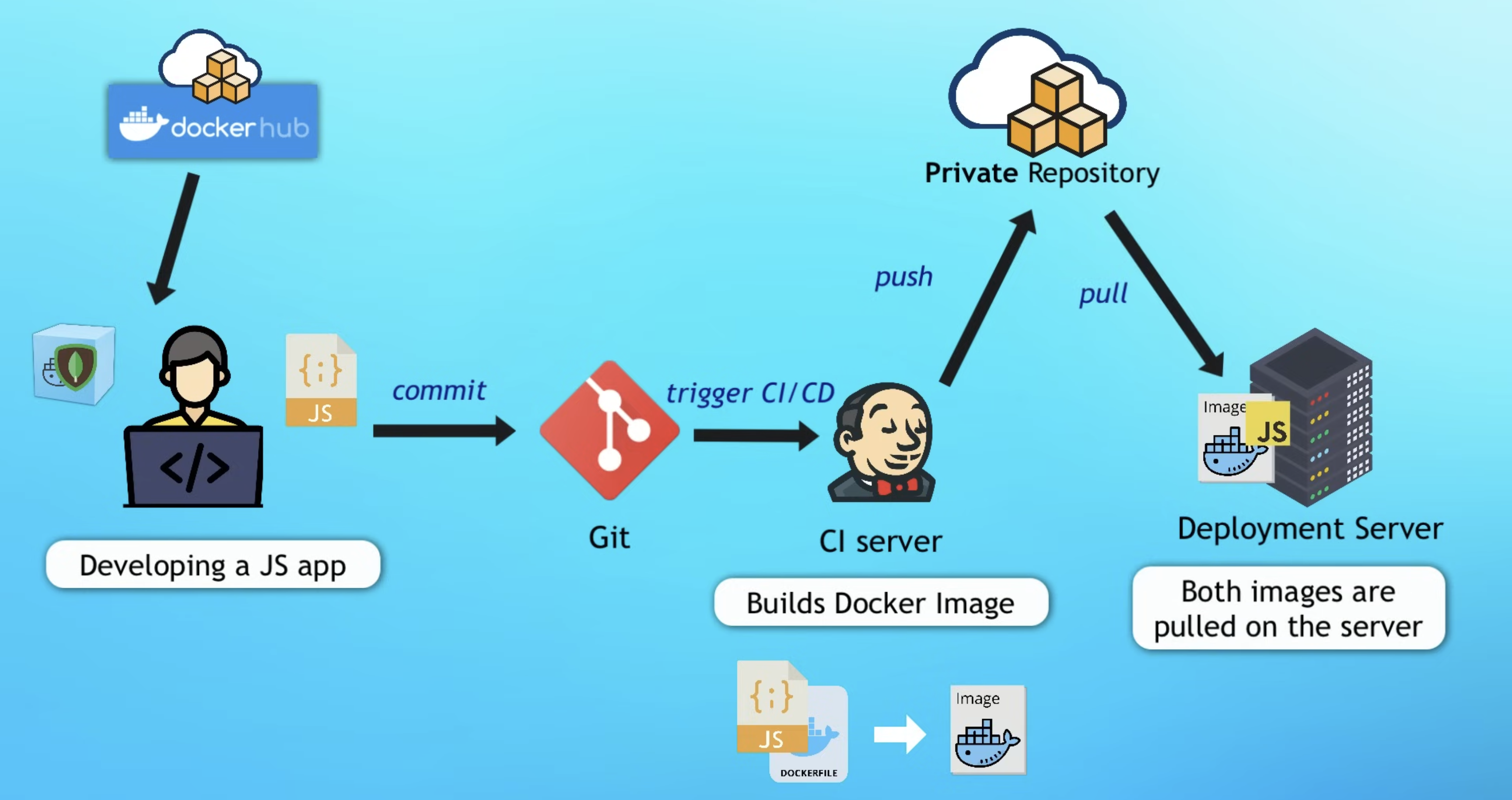

Big picture view of Docker in Software Development Cycle

Image → Container (build → run)

flowchart LR DF[Dockerfile] -->|docker build| IMG[(Image)] IMG -->|docker run| C1{{Container}} IMG -->|docker run| C2["Container<br/>(another instance)"]

Registry → Repository → Tag

flowchart TB REG["Registry<br/>Docker Hub / Private Registry"] --> R1[Repository: nginx] REG --> R2[Repository: myapp] R1 --> T1[Tag: 1.23] R1 --> T2[Tag: 1.23-alpine] R1 --> TL[Tag: latest] R2 --> A1[Tag: 1.0] R2 --> A2[Tag: 1.1]

Build → Push → Pull → Run (distribution loop)

flowchart LR DEV[Developer / CI] -->|docker build| IMG[(Image)] IMG -->|docker push| REG[(Registry)] REG -->|docker pull| HOST[Server / Laptop] HOST -->|docker run| CTR{{Container}}

Docker Architecture: End-to-End

Open in new tab (*Note: Best viewed in desktop or landscape view*)Why Docker exists (What problem does it solve)?

Software doesn’t “run” from source code alone. It runs from code + runtime + OS libraries + configuration + dependent services (Postgres/Redis/etc).

“Works on my machine” happens when those hidden assumptions differ across laptops and servers (versions, configs, OS differences).

Docker’s core move is simple:

Instead of shipping code + instructions, ship code + environment.

Deployment process before and after Docker containers

Deployment process before Containers

Textual guide of deployment (Dev → Ops)

- ❌ Human errors can happen

- ❌ Back and forth communication

Deployment process after Containers

Instead of textual, everything is packaged inside the Docker artifact (app source code + dependencies + configuration)

- ✅ No configurations needed on the server

- ✅ Install the Docker runtime on the server (one-time effort)

- ✅ Run Docker command to fetch and run the docker artifacts

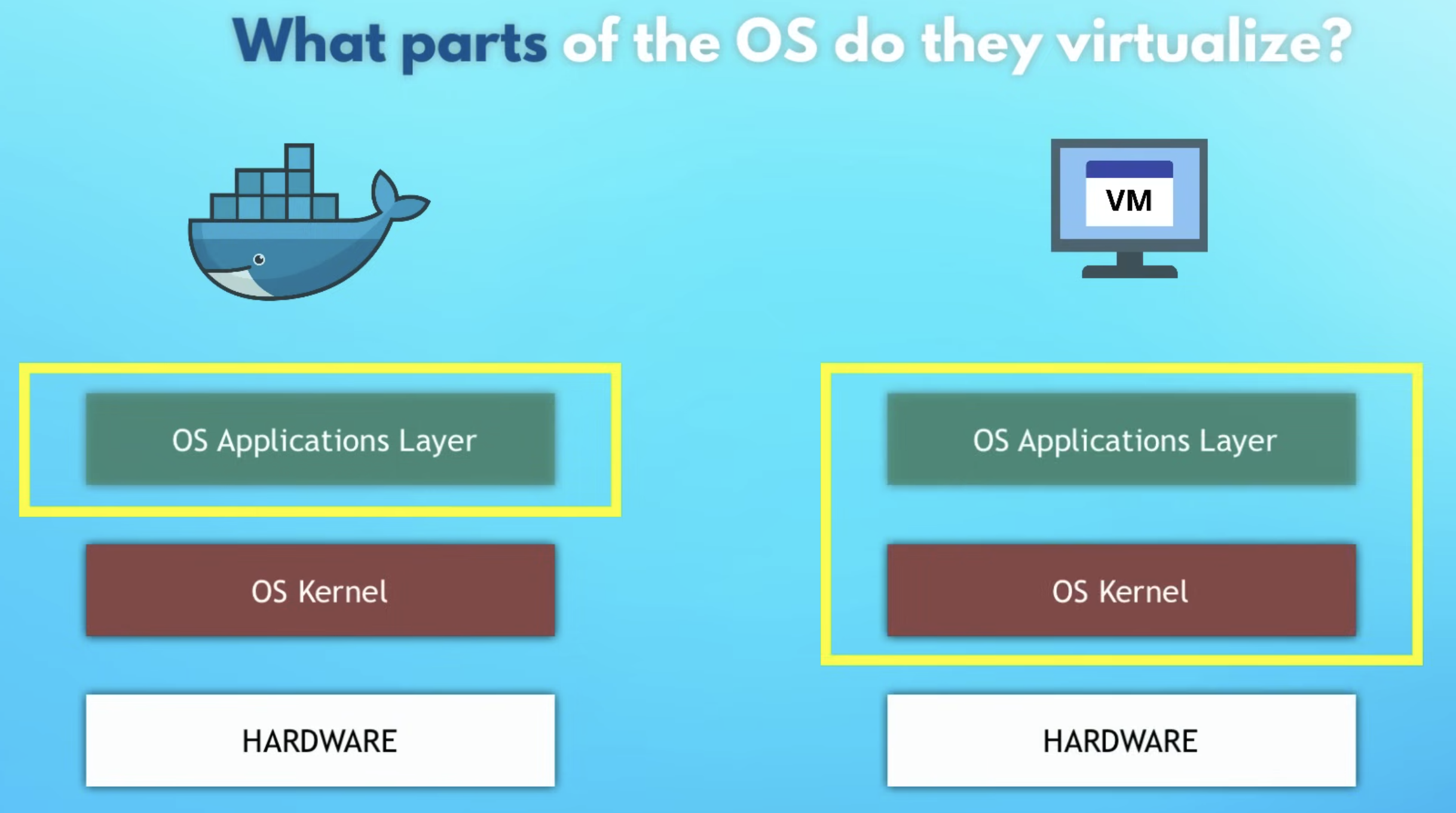

What Docker really virtualizes (VMs vs containers)

First principles: an OS has two “layers”:

- Kernel: talks to hardware (CPU, memory, disk).

- User space: programs + libraries that run on top of the kernel.

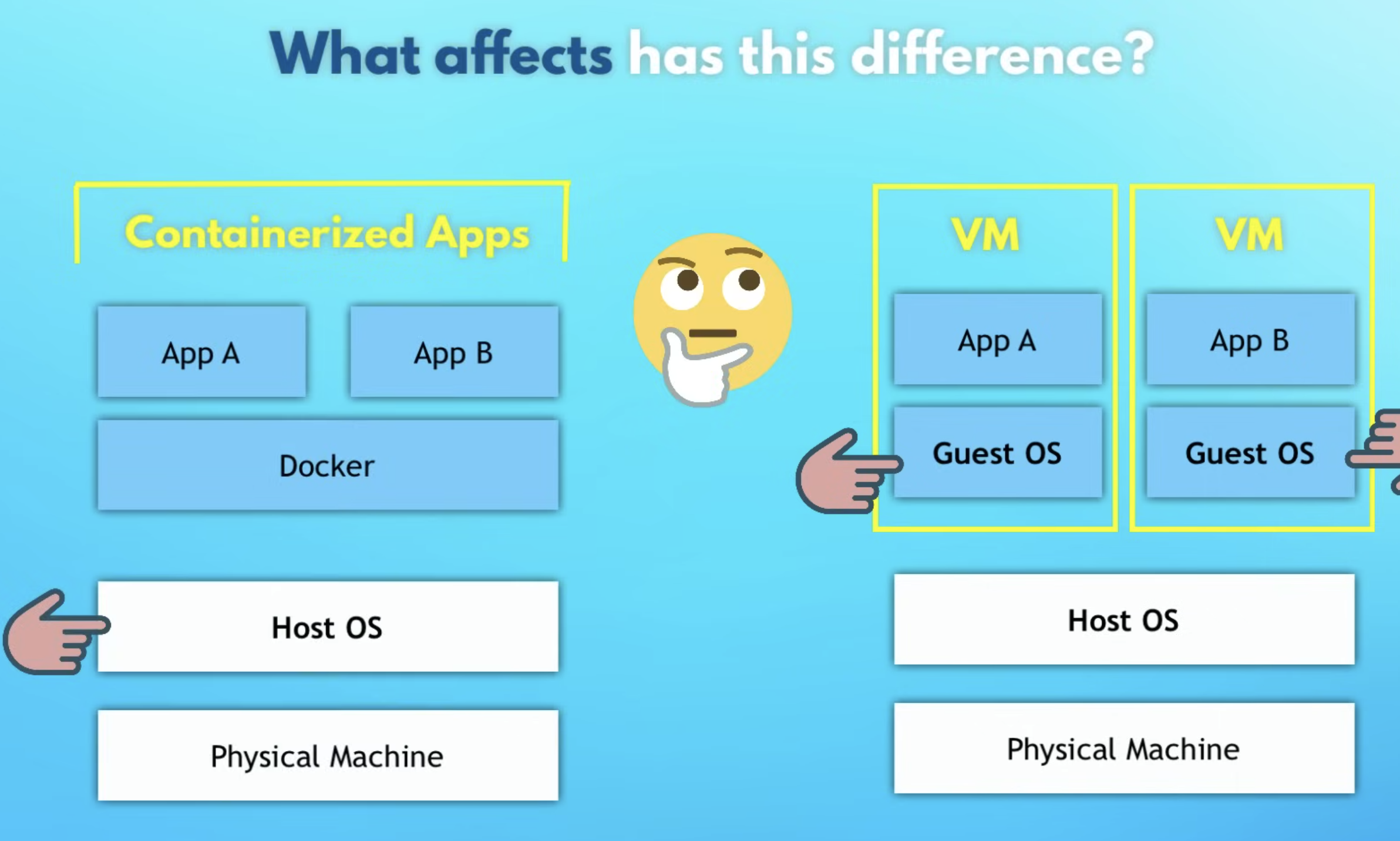

Docker vs VMs differs mainly in what gets virtualized: the whole OS, or just the application user space.

Virtual Machines (VMs)

- Virtualize kernel + user space (a whole OS)

- Heavier (GBs), slower start (often minutes)

- Strong isolation; can run different OS kernels (Linux VM on Windows host, etc.)

Docker containers

- Virtualize user space (process + filesystem + libs)

- Reuse the host kernel

- Lighter (MBs), faster start (often seconds or less)

On macOS/Windows, Docker Desktop runs a lightweight Linux VM under the hood so Linux containers can still run — that’s why it “just works” locally.

The 4 core nouns: Image, Container, Registry, Repository

1) Image = the package

An image is the immutable artifact you build or download: app code + runtime + OS user-space bits + config.

2) Container = a running instance

A container is a running (or stopped) instance of an image — like “a process with a filesystem snapshot”.

Analogy:

- Image: blueprint / recipe / “frozen meal”

- Container: built house / cooked dish / “hot meal”

3) Registry = the image warehouse

A registry is a service that stores images and lets you pull/push them.

- Public registry: Docker Hub is the default public registry most people start with.

- Private registry: companies store internal images in private registries (cloud provider registries, self-hosted, or private Docker Hub repos). Registries exist because images are large and versioned, and need standardized distribution (pull/push), caching, and access control across laptops, CI, and servers.

4) Repository = a folder inside a registry

A repository is a named collection of related images (usually one app/service).

Think:

- Registry: the warehouse

- Repository: a shelf (one product line)

- Tags: labels on boxes (versions)

Tags and versioning (why latest is usually a trap)

Images are referred to as:

name:tag

Examples:

nginx:1.23node:20-alpine

What latest actually means

latest is just a tag — not “the newest stable thing” by magical guarantee.

Best practice: pin explicit tags (or digests) in production and CI.

Hands-on Lab 1: Run a container (nginx) and actually reach it

This mirrors the flow from the crash course: pull → run → port-bind → inspect logs.

Step 1 — Pull an image (optional, docker run can auto-pull)

docker pull nginx:1.23

docker imagesThis downloads the image locally. At this point, nothing is running yet — you’ve only stored the artifact.

Step 2 — Run a container

docker run nginx:1.23You’ll see logs because your terminal is “attached” to the container process.

Step 3 — Detached mode (get your terminal back)

docker run -d nginx:1.23

docker psStep 4 — Port binding (make it reachable from your laptop)

Core idea:

Containers live behind Docker’s networking boundary. Port-binding is you punching a controlled hole from host → container.

flowchart LR B[Browser] -->|localhost:9000| H[Host OS] H -->|publish 9000:80| D[Docker Engine] D -->|to container port 80| C{{nginx container}}

Bind host port 9000 to container port 80:

docker run -d -p 9000:80 nginx:1.23

docker psNow open: http://localhost:9000

Why this works?

localhostis your host machine. The container’s port80is private unless you publish/bind it to a host port.

Step 5 — Logs, stop/start, and the “where did my container go?” moment

docker logs <container_id_or_name>

docker stop <container_id_or_name>

docker ps

docker ps -adocker psshows running containers.docker ps -ashows all containers (including stopped ones).

Restart an existing container (no new container is created):

docker start <container_id_or_name>Step 6 — Name containers (humans > IDs)

docker run -d --name web-app -p 9000:80 nginx:1.23

docker logs web-appHands-on Lab 2: Build our own image (my docker-demo workflow)

My demo repo is the canonical “smallest useful Dockerfile” exercise: a Node app with src/server.js and package.json, packaged into an image and run as a container (repo).

Think like Docker: what must be true for this app to run?

Requirements:

- Runtime exists:

nodeis available - Dependencies are installed:

npm installhappened during image build - Files are present:

package.jsonandsrc/are copied into the image - Working directory is consistent: pick a stable path (commonly

/app)

Minimal Dockerfile (explained by “mapping local steps”)

If your local steps are:

npm install

node src/server.jsThen your Dockerfile should encode the same:

FROM node:20-alpine

WORKDIR /app

COPY package.json /app/

COPY src /app/

RUN npm install

CMD ["node", "server.js"]Intuition:

FROMselects a base image that already has the runtime installed.WORKDIRmakes paths stable and predictable.RUNexecutes at build-time (creates layers).CMDis the default run-time command when the container starts.

sequenceDiagram participant You as You participant Docker as Docker Engine participant Img as Image participant C as Container You->>Docker: docker build ... Docker->>Img: FROM/COPY/RUN (build layers) You->>Docker: docker run ... Docker->>C: create container from image Docker->>C: CMD (start process)

Build the image

From the directory containing the Dockerfile:

docker build -t docker-demo-app:1.0 .

docker imagesRun it (and bind ports)

If the Node server listens on 3000 inside the container, bind it to 3000 on your host:

docker run -d --name docker-demo -p 3000:3000 docker-demo-app:1.0

docker ps

docker logs docker-demoOpen: http://localhost:3000

Shortcut:

docker runwill auto-pull from Docker Hub if the image isn’t local. For your own image, it’s local unless you push to a registry.

Where Docker fits in the bigger workflow (dev → CI → deploy)

The “big picture” loop:

- Dev: run dependencies (DB/Redis/etc) as containers; keep your laptop clean.

- Build/CI: build a versioned image from your app (

docker build ...). - Registry: push to a private repo (

docker push ...). - Deploy: servers pull the exact image version and run it (

docker run ...or an orchestrator).

flowchart LR subgraph Local[Local development] APP[App code] --> DEPS["Dependencies as containers<br/>(DB/Redis/etc)"] end APP -->|git push| GIT[(Git repo)] subgraph CI[CI pipeline] GIT --> BUILD[Build + Test] BUILD -->|docker build| IMG[(Image)] IMG -->|docker push| REG[(Private Registry)] end subgraph Env[Environments] REG -->|pull + run| DEVENV[Dev] REG -->|pull + run| STG[Staging] REG -->|pull + run| PRD[Prod] end

Net effect: you stop re-implementing “installation + configuration” as a fragile checklist on every machine; the image becomes the executable contract.

Dockerfile intuition: layers and caching

Each FROM, COPY, RUN creates an image layer.

Docker caches layers. If a layer doesn’t change, it reuses it.

Practical implication:

- Copy

package.jsonfirst, runnpm install, then copy the rest — so dependency install is cached unless dependencies change.

flowchart TB L1[Layer: FROM node:20-alpine] L2[Layer: WORKDIR /app] L3[Layer: COPY package.json] L4[Layer: RUN npm install] L5[Layer: COPY src/] L6[Layer: CMD ...] L1 --> L2 --> L3 --> L4 --> L5 --> L6 S1[Change: src/] -->|rebuild from L5| L5 S2[Change: package.json] -->|rebuild from L3| L3

Compose (why it exists)

docker run ... is great for 1 container. Real apps are usually multiple containers:

- app + database + cache + queue + …

Docker Compose is a “runbook you can execute”:

- defines containers, ports, env vars, volumes, networks

- lets you bring a whole stack up/down predictably

Think of Compose as “a declarative script for

docker runcommands”.

Volumes (data that must survive containers)

Example mental model:

- Container filesystem: throwaway

- Volume: durable attachment you can remount to new containers

Best practices (high signal)

- Pin versions: prefer

postgres:16overpostgres:latest. - Name containers: it makes logs and scripts sane.

- Prefer immutable builds: configure via env vars/volumes, not manual changes inside a running container.

- Don’t store secrets in images: inject via env/secret managers.

- Clean up: stopped containers and unused images accumulate.

Mental Model Cheat Sheet

- The Difference:

venvorganizes the Bookshelf (Python libraries), but Docker builds the Entire Apartment (OS tools, system libraries, and settings). - The Engine: Docker is fast because it shares the Host Kernel while isolating the User Space.

- The Lifecycle:

- Dockerfile: The Recipe

- Image: The Frozen Meal (Blueprint)

- Container: The Hot Meal (Running Instance)

- The Manager:

docker-composeis the Waiter/Tray coordinating multiple dishes (services), ports, and volumes.

Next Steps

Docker Compose Kubernetes (K8s)

Appendix: Self-check Q&A (Socratic questioning)

- What does it mean for software to “run”?

- Code + runtime + OS libs + config + dependent services.

- Why does “works on my machine” happen?

- Environment drift: different versions, configs, OS behavior.

- If an image is immutable, what is “running”?

- A container is the running (or stopped) instance of an image.

- Why do registries exist?

- Distribution + caching + access control for large, versioned artifacts.

- Why can’t I access a container port directly via

localhost?- Container networking is isolated; you must publish/bind ports from host → container.

- Why do we use

CMDinstead ofRUN node ...?RUNhappens at build-time;CMDis the default runtime command.

- If containers are disposable, where does persistent data go?

- Volumes (or external managed services).